|

Africa Agriculture - Nutrition | Science - Education | Environment - Nature African climate change: Blooming Sahara or hunger and war?

The most known scenarios of Africa's future in a warmer world include more drought, floods, cyclones, land degradation, epidemics and resource wars. A negatively changing climate always will have the greatest effects on the poor and on societies living directly from earth resources, making Africa most vulnerable to even small reductions in rainfall or increases in extreme weather frequency.

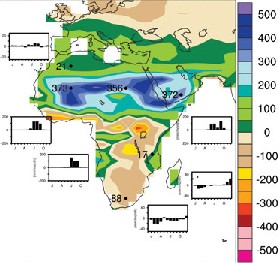

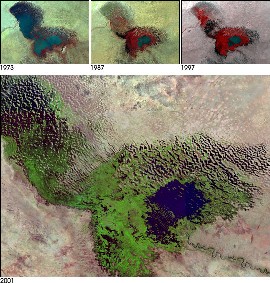

During the early and mid Holocene - corresponding with the first millennia after the latest ice age - the global climate was about 2-5 degrees warmer than today. In some regions this meant a drier climate, but for most of Africa, it meant more rain and more stable rainfalls. In the northern half of Africa, this meant that the African monsoon went much further north and especially the Central Sahara had a moister climate. But also south of the Sahara, rainfall was more abundant, meaning that the forested region went further north. These are the most certain data from the Holocene Climate Optimum, and other African regions have been much less studied (Africa's climate as a whole has been less studied than other regions). There are however indications that the Holocene greening included the African Horn, Southern Arabia and East Africa. According to the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine, "East Africa was much wetter during the early Holocene than it is today," but the region does not always follow the warm-wet, cool-dry pattern. Data on Central Africa are sparse, some indicating drier conditions in today's Congo Basin and some indicating even more rain. Only Southern Africa seems certain to have been much drier each time the historic climate has become warmer. "The early Holocene experienced warm and extremely dry conditions," according to a study by the European Geophysical Society. Southern Africa is also the most frequently mentioned example of current negative effects of global warming in Africa with an increased drought frequency. The big question that has been astonishingly little studied is whether the ongoing man-made climate change will lead us back to the conditions of the mid-Holocene if or when we reach the same temperatures. Can we predict that at least the northern half of Africa will be much better off by global warming, while we need to assist Southern Africa in restructuring its agriculture to drier conditions? Most climate models trying to predict the effects of global warming indeed calculate with a marginal or small increase of rainfall in the northern half of Africa. But these models, that are not so much based on paleoclimates, mostly hold that this increase is within the error margin, and many also predict a northwards move of the Sahara, meaning that the African and European Mediterranean could face desertification. But they do agree on a much drier climate for most of Southern Africa and indicate that East Africa could follow the same negative path. These models and current experiences could point to a very negative conclusion on climate in a warmer Africa. One already sees a deteriorating climate in Southern Africa, which has contributed strongly to food insecurity in the region. Most observers hold this is a direct consequence of global warming. But the positive effects are not that visible. Why, for example, is Lake Chad still shrinking when it was a mega-lake in the Holocene? Will we fail to obtain the positive effects of global warming in the Sahel and Sahara? Experts in paleoclimate are however more optimistic about the northern half of Africa - for other parts of Africa they lack good data. The Saharan climate, sediment cores from Mauritania have shown, is twisted between two extremes: It either is green or it does not support vegetation. There is a threshold to be crossed, or at least, that was the case in the Holocene. Scientists have shown that, when the greening first starts due to some more rainfall, veget

Martin Claussen of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology has looked deeper into the possible "greening of the Sahara" due to global warming. He concludes that "some expansion of vegetation into today's Sahara is theoretically possible" as a consequence of CO2 emissions. Indeed, "the rate of greening can be fast, up to 1/10th of the Saharan area per decades," his models had shown. But he warns against believing the mid-Holocene climate optimum will be recreated. Firstly, it is not the same processes driving today's climate change, meaning that they may not have the same effect on ocean currents, insulation and thereby rainfall patterns. Further, and more important, today's Sahelian landscape is also strongly shaped by man-made factors such as over-grazing. In short, if pastoralists follow their cattle into greening areas, they may destroy the potential effect vegetation could have on the climate, thus hindering the positive development to get rooted. These warnings by Mr Claussen may be a much underreported issue, as satellite images of the Sahel indicate that the southern edge of the Sahara already may have experienced a small greening effect. But these areas are also under heavy pressure by a rapidly growing population, which may be hindering the full and spreading effect of greening. In fact, the same region is subject to deforestation, countering the possible positive effects. The increased use of water in this region also partly explains the continued shrinking of Lake Chad. If the paleoclimate specialists' models are to be believed, there are new challenges for Africa as it develops a new climate. There is an almost universal agreement on a drier climate in most of Southern Africa, which must be addressed by helping the region to become less dependent on rain-fed agriculture. In the Sahel, on the other hand, there are strong indications that very positive climate effects can be yielded if the fragile ecosystem is let to cross the greening threshold. With an optimal development, Niger, Mali and Mauritania could become the bread baskets of Africa in some decades. But the great problem is that so little research has been done on how to meet these climate challenges. For East and Central Africa, there are not even sufficient paleoclimatic data to be able to make good models for a warmer future. And for the northern half of Africa, there are very few studies looking into what is actually happening. Is the region greening or drying up? Is the desertification effect of a growing population reversing a possible greening? How should we act to help a possible greening effect to spread more rapidly? The irony is that large parts of Africa could indeed face a positive effect of global warming, but due to lack of research, we may never know. As the world gets ever more determined to stop an uncontrolled global warming, the possible negative and positive effects of this climate change on Africa need to be better researched. Surely, in many African countries, great efforts will be needed to reverse the droughts, floods, epidemics and coastal erosion inflicted by CO2 emissions from the industrialised world. But even these consequences are too poorly mapped, and scientists warn that time is running out. By Rainer Chr. Hennig © afrol News - Create an e-mail alert for Africa news - Create an e-mail alert for Agriculture - Nutrition news - Create an e-mail alert for Science - Education news - Create an e-mail alert for Environment - Nature news

On the Afrol News front page now

|

front page

| news

| countries

| archive

| currencies

| news alerts login

| about afrol News

| contact

| advertise

| español

©

afrol News.

Reproducing or buying afrol News' articles.

You can contact us at mail@afrol.com